Free List: How to Help My Child Stop Stuttering

Is your child getting stuck when they try to talk? Do you wanna know you can do to help right now?

Well, if they’re between the ages of two and six years old, I’m gonna tell you right here.👇

I’m Stephen, a successful person who stutters, speech pathologist, and dad of a three-year-old daughter who stuttered.

Below is the most comprehensive (but readable!) list of ways you can help your preschool child stutter less and speak more easily that you’ll find anywhere on Google, with practical examples and a link to their sources.

Got a pen? ‘Cause you’re gonna want to take notes.

(Full Disclosure: if you like all the value you find in this page you can invest in my full “Stuck to Speaking” course at the bottom. If not, I’m just happy to share all this goodness with you and hopefully help you feel a little bit better.)

So, What Exactly IS Stuttering?

It’s when one’s normally effortless, forward-moving speech gets stuck, leading to involuntary disfluencies like r-r-repetitions, prrrrrrrolongations, and/or b___locks as one tries to keep moving.

(Abnormal muscle tension, speech timing, and a feeling of being out of control are also often present).

But I like to say stuttering is when “your words get stuck."

I-i-i-if yyyyyou h-hear a llllllllllot of th—is in-in your ch—ild’s s-s-speech, they're l-likely ssssssstuttering.

These “stuttering-like disfluencies” are the hallmark of stuttering and are what are used most commonly to diagnose stuttering.

How Common Is It?

Eight to 10% of children stutter somewhere in their childhood, usually between the ages of two (when they start putting two words together) and four. Fifty percent of the onsets are described by parents as “gradual” and 50% as “sudden.”

Roughly 85% of those children will recover within three to four years or usually by age seven, with more girls recovering than boys.

About 15% of these children who start stuttering will not recover, however, leaving almost 1% of the general population to stutter throughout their lives. That’s about 70 million people worldwide, or the entire population of California, Texas, and Georgia COMBINED.

Lifelong stuttering often leads to psychological, social, and work difficulties.

What Causes Stuttering?

While we don’t know what causes it with 100% certainty yet, we do have a pretty good guess:

There’s a neural loop in our brains responsible for timing the release of motor commands to our muscles when we talk that’s called the “cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop” (long name I know; don’t be scared). It simply runs from the language areas of the cortex down through the basal ganglia, to the thalamus, then back up to the cortex. And it basically produces the “drumbeat,” or internal rhythm, to our speech.

Research has shown that children who stutter have more difficulty producing these internal timing cues than their peers who don’t stutter.

So what goes wrong? Well, it starts in our genes. Genes account for 80% of starting to stutter, and while many genes have been implicated in stuttering, gene “GNPTG” may be one of the most important ones yet.

It’s responsible for directing cellular traffic in brain cells’ trash and recycling systems (called the “endosomal-lysosomal system”) of the “cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop,” and, in children who stutter, gene GNPTG doesn’t seem to work as well.

We think this probably leads to a buildup of cellular “trash” inside the neurons of that important speech timing loop, causing slower and less accurate signals that reduce its ability to produce the necessary internal timing cues during speech.

Alright, I just took you down a deep dive of neuroanatomy in just nine sentences. If your head’s spinning, never fear: I break this all down in an insane amount of detail inside my “Stuck to Speaking: A How-To Handbook For Parents of Preschoolers Who Stutter,” which you can get here, so you can get all the info you want on this.

What Can You Do to Help?

Start Keeping Track

The verrrrrrry first thing you should do is to start keeping track of a few key variables so you can see how your child’s stuttering changes over time. This’ll help you know if what you’re doing is working, when it’s time for you to get more help, and greatly help professionals if you ever go and see them.

Track these three things:

1. Time Since Onset

This is how long it's been since your child first started stuttering. Just try to remember when you first noticed your child stuttering and write it down. (It can be helpful to try to remember any holidays, seasons, or big life events surrounding the onset to try to pinpoint it). If you really can't remember, guess-timating to the nearest six months will still be hugely helpful (e.g. 2-, 2½-, 3-, 3½-, or 4-years-old).

2. Stuttering Severity

The most important metric you can track over time is your subjective rating of your child’s “stuttering severity” on a 10-point scale by answering the question, “How severe is your child's stuttering, with 0 being ‘no stuttering,’ 1 being ‘extremely mild stuttering’ and 10 being ‘extremely severe stuttering?’”

While tracking their stuttering severity every day would be the most informative, that's not realistic for very many of us busy parents, so logging this rating at the same time once a week, every week, is still hugely valuable.

3. Parental Concern

Lastly, as your child's caregiver, your gut instinct and intuition are extremely valuable. Secondary to your child's stuttering severity, track your level of concern by answering the question, “How concerned are you about your child and their stuttering on a 10-point scale, with 0 being ‘not concerned at all’ and 10 being ‘extremely concerned?’” at the same time your rate their stuttering severity.

If you want the crisp Stuttering Tracking Sheet I give my clients, find it on page 26 of my “Stuck to Speaking Handbook” here.

Slow Down Your Own Speech

The next thing you can do to help your child speak more easily is not to try to change their speech at all. It’s to change yours. If you make the environment they speak in easier, their speaking will get easier too.

So first: slow down your own speed of speech when you talk to your child. That gives their brain has more time to speak and they get a good model of what a smoother, more fluent way of speaking sounds like. You can try it in three ways:

1. Slow Down to 75% Speed

Consciously slow down your words a notch or two as you speak, to about 75% speed:

“Soinsteadoftalkinglikethistellingthemaboutgoingtoseegrandma…”

“Taalk a bit more liike this, taking more tiime to speak more comfortably aand slowly.”

Go ahead and try it (yes, out loud!). Say your full name and birthday at about 75% speed.

I’ll wait. (Still waiting).

Good! Now, do it again, this time saying your child’s full name, their birthday, and your address at 75% speed.

You’re nailing it! Just take your foot off the gas a little bit and you’ve got it.

2. Add More Natural Pauses

A second way to slow down your speech is to insert more pauses in natural places (where you’d normally put a comma) and hold them for a beat longer than you normally would.

You don’t have to slow the actual formulation of your words down for this one, but you’ll end up slowing down your sentence as a whole by adding in more pauses throughout.

“Soinsteadoftalkinglikethisandneverputtinginabreak..."

“Talk more like this (with normal speed words) ... with slight pauses sprinkled in … giving your speech a more easy … relaxed … and open way about it.”

Go ahead and try it aloud, saying what your job is and what one of your favorite hobbies is. Remember, just add a pause where there’d normally be a comma and hold it for two beats instead of one.

I'll wait.

Suhweet! Now do it again, this time saying what one of your favorite things is about your child.

Ready for number three?

3. Reflect Their Speech Back More Slowly

Another big way you can slow down your speech is to model your child’s stuttered speech back to them at a slower speed once they’ve finished, making it a part of the conversation but saying it in a very slow, easy, and relaxed way.

If they say, “Mommy, I-i-i-iiiiiiii want to p-play, um, I want to p-play, um, rrrrrrracecars!”

You could say (slowly) “Oh!…you want to play…racecars…huh?”

Easier. Gentler. Smoother. Basically, you want to do everything you can “take your foot off the gas” when speaking with your child who stutters. Just like you would if you saw an accident about to happen on the highway, easing off the gas in your conversations can help things to flow more smoothly.

Okay, now you try it. For the next three hurried, stuttered, tense sentences your child says, try repeating them back to them at a slower, easier rate and see how it feels.

There’s a fourth technique I use to slow down your speech when talking to your child who stutters and you can find it on page 32 of my “Stuck to Speaking” handbook here.

Here’s a source, and another, and another.

Reduce Talking Demands

As a child, talking comes with a lot of demands, like talking when listeners are in a hurry, learning to say more and more grammatically-complex sentences, or talking while worked up over a lost toy.

Reducing these talking demands helps sweeten the speaking environment by dialing the stress of speaking waaaaaaaay back, so your child can speak more easily.

I like doing this in two big ways:

1. Reduce "Rush"

Number one: don't finish their sentences, even if they’re stuttering. While this does come from a place of wanting to be helpful, guessing what your child is going to say and finishing their sentence for them tells them you don't have time for them to get their words out. It implicitly ratchets up time pressure, which will likely lead to more stuttering. Unless they specifically ask you to, don't finish your child's sentences for them. Instead, give them as much time as they need (as is realistically possible) to get them out.

Leave a brief pause in between turns in the conversation. When your child asks or says something, leave a thoughtful, unhurried pause for an extra beat before you start to respond to them.

Give full attention when you can. I know being a parent can be busy. But nothing tells a child they have to work harder to be heard more than talking to a distracted listener. That's why, as much as is realistically possible, give your child full attention in conversation. That means no thinking about what needs to go on the grocery list, if you switched the laundry yet, or what you'll ask your boss tomorrow, just fully committed, in-the-moment time with them.

2. Don't Put Them "In the Hot Seat"

Putting children who stutter "in the hot seat" to speak or perform can really increase speaking stress, and thus, stuttering. Here are a few ways to cut it out:

Comment on things instead of interrogating. We've all done it. We've been playing with our little one and thought we might start SAT prep early. "What's this?" "What color is that?" "What sound does a cow make?" "Who's this?" "What does a pirate say?" And while it comes from a good place, it can put a LOT of pressure on your young child who stutters.

Instead, comment on all those things instead of grilling your little one. Like this: "This is a cat!" "That dog is brown." "A cow says, 'Mooooo!'" "This is a pirate." "He goes, 'Arghhhhhh!'" Your child still gets all the good language input, but the communication pressure isn't anywhere near boiling.

Don't make them perform. Say you're over for dinner at Grandma's and, to make conversation, you ask your young one to “tell Grandma what you did yesterday!” And your child's eyes grow wide and they look around before stuttering their way halfheartedly through an escapade.

Instead, discard the expectation that they perform for everyone and anyone. Only make them perform if they want to.

I teach a third way to reduce talking demands on page 36 of my “Stuck to Speaking Handbook” (with demo videos if you opt for the Platinum version), which you can get right here.

Here’s your sourcie-source. And a second.

Celebrate Easy Speech

Every child who stutters, even the ones who stutter the most severely, says some things fluently. When they do, celebrate that with them, point it out, cherish it, and reinforce it. Praise your child for any easy, stutter-free speech they have. This external feedback can help nudge their brain to speak more fluently without them having to consciously do anything at all.

The exact wording is going to come down to what you feel comfortable with and what your child's the most responsive to. You know your child best and should lean into that intuition. But here are some examples of what you can say:

“That seemed so easy for you to say, way to go!”

“Wow, that all came out so smoothly! You should be impressed with yourself.”

“None of your words got stuck there, man. I'm happy for you!”

“You just said that without stuttering at all! Must feel great.”

These responses help first to normalize stuttering and make it something that gets talked about (which is rare in our culture), and then encourage brain change towards fluent speech by providing positive reinforcement for it in everyday life.

Find three more examples of what you can say on page 39 of “Stuck to Speaking.”

Here’s a source for this technique. And another.

Talk to Your Child About Stuttering

Let’s talk about the “S” word. Most times, we can’t really bring ourselves to say the word “stuttering.'“ But you know what that tells our children, when we can’t even bring ourselves to say the word?

That it’s so bad that it can’t even be talked about.

It can’t even be spoken.

And that makes it 100x worse. “Hmm…it’s so bad we can’t even talk about it? Must be REALLY bad.” While we often don’t want to “make it worse” by talking about it, but by not talking about it, we unintentionally make it worse. When you treat it just like anything else, though, the fear just sort of melts away.

How can you do that?

You talk about stuttering just like anything else that’s not the most fun, like:

Pulling off a Band-Aid®

Losing a favorite toy

Scraping your knee

Getting a shot

Wetting the bed

Spilling your juice

You name the not-so-fun thing, maybe name a feeling they might be having, and soothe with love, support, and hope, right? And that’s exactly how you should talk about stuttering:

“That seemed like it got stuck in your mouth. That’s no fun.”

“I love hearing what you have to say, no matter if it gets stuck coming out.”

“When your words get stuck in your mouth it’s called stuttering. We’ll find a way to make it easier together.”

Start off by really believing that the word “stuttering” isn't a curse word. You can say it. In fact, you should say it aloud if that’s what’s going on.

For young children who stutter, I usually make sure we talk about three things:

1. Stuttering's Definition

For very young children, I use a simple but true version of the definition of stuttering:

“When your words get stuck in your mouth like that, it's called ‘stuttering.’”

“Your brain's working hard to keep time for all your words. When it gets stuck, that's called “stuttering.’”

2. That They're Not Alone

I always also normalize stuttering as something that many children experience:

“Many children stutter while their brains learn how to speak.”

“About one in every ten kids stutter as they learn how to talk.”

3. Their Frustration (When it's Exhibited)

Whenever a child shows visible signs of frustration when they're speaking, it's important to acknowledge it and provide some support:

“I can see you might be a little frustrated about how hard that story was to get out. I'm here. Know I love what you have to say, no matter how it comes out.”

"You're allowed to be frustrated. That sounded hard."

4. Three Big “No-No’s” When Talking to Your Child Who Stutters

When we see (or hear!) our child struggling, our first instinct as parents is to jump in and try and fix it. In the case of stuttering, though, some of the common “fixes” we naturally jump to don’t always help.

Here’s a list of a few:

Don’t tell your child to “just slow down.” Instead, model a slow, unhurried speed yourself. They’ll follow your lead.

Along the same lines, don’t say the common but trite “just take a breath,” “think about what you want to say,” or “calm down” tips. While well-intentioned, they can actually increase the pressure the child feels while speaking.

Lastly, don't just NOT talk about stuttering with your child if that's what they're experiencing. Not talking about makes it taboo and 1000x scarier. Remember, stuttering isn't a curse word. You should talk about it if that's what's going on.

Now, if your child’s stuttering with you, they’re most likely stuttering in front of their friends and family too. I’ve got a whole script of what you can say to them about your child’s stuttering inside my “Stuck to Speaking Handbook” right here.

Do “Beat Speech” Workouts

“Beat Speech,” known in the scientific literature as “syllable-timed speech” is a pattern of talking where you "break- up- each- word- in-to- its- sy-lla-bles- and- say- each- one- with- a- strong- beat. Keeping as near-normal of a speed and intonation as possible, you build in the absent rhythm into the words themselves.

Having “Beat Speech” workouts for 5-10 minutes a few times a day for nine to twelve months has been found to reduce stuttering a LOT in preschool children who stutter, even up to 96%!

Now, this isn’t meant to be a new way that your child speaks 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. It’s only intended to basically be a daily “speech workout” for five minutes, about five times a day (a total of 20-30 minutes per day) and used during especially difficult stuttering moments if they want to. That’s it.

It's also meant to be done as naturally as possible, with a near-regular of a speed and normal speaking intonation, simply adding de-fi-nite- bound-aries a-round- each- sy-lla-ble (see how fast you can do it while still putting in a strong beat).

Last tip: when you practice it, you both have to do it. You have to be all in for your child to buy in too. While it might feel slightly weird at first, it'll quickly become second-nature.

Now, I’d highly recommend getting my “Stuck to Speaking Platinum” course so you can watch me do this on video or that you work with an experienced speech pathologist for this one, since it’s a little more technical than the others.

Here are the important sources: here and here.

Build Emotional Self-Regulation

We know the root cause of stuttering isn't simply “being nervous” (as is commonly thought), but big emotions do seem to make stuttering worse.

While a little bit of stress can be a good thing, (needed when you have to outrun a pouncing tiger), chronic, unrelenting stress can deplete a child's internal resources needed to function optimally.

And one of the things that can be affected is a child's speech system. Environmental stressors interact with their brains, exacerbating any weaknesses already present. If a child's genes predispose their brains to having weaker internal timing abilities during speech, that weaker speech system will perform even more poorly in the face of challenging environmental stressors, like competing with an older brother for attention or during the crazy fun of a friend's birthday party.

So how can you help strengthen your child’s emotional self-regulation that can buffer them against stressors that make speaking more challenging?

1. Sight Symptoms of Stress

Watch for signs that your child is having a hard time: difficulty handling big emotions, difficulty paying attention to you or important things around them, withdrawing socially, showing increased physical tension, having an accelerated heart rate, being anxious, or making impulsive decisions, etc.e

You know your child the best. Lean into that intuition and trust your gut.

2. Identify the At-Fault Stressors

Next, identify what environmental stressor(s) may be causing your little one to be so emotionally reactive.

Here’s a table of some common stressors you’ll find inside my full “Stuck to Speaking Handbook,” which you can get here.

3. Help Co-Regulate Your Child

When we hear the word "self-regulation," we often think it's the responsibility of the child to know how to return themselves to homeostasis. But in reality, children actually learn to self-regulate over time through many instances of co-regulation with us adults!

I've condensed the co-regulation research into four major principles you can follow to help co-regulate your child who stutters and return them to homeostasis so they can speak the most easily. They can be done both during a moment of stuttering or whenever they're highly emotionally reactive. Click here to see the breakdown on pages 67-68 of my “Stuck to Speaking Handbook.”

4. Teach Emotion Awareness

Putting our emotions into words is one of the easiest and quickest ways to increase our emotional regulation.

Scientists have found that by simply naming a negative emotion out loud in words, brain activity in our amygdala (the emotional processing hub in the brain) is basically cut in half, with a large effect size of .87.

So, how do you teach your children how to put their emotions into words? You do it for them at first:

In Yourself

“MaMa just gave me a new standup mixer for Mother's Day and I can't stop smiling! I'm so excited to make some fresh bread with it.”

“Whew, my heart is pounding so hard right now. That car almost hit us and I'm mad they weren't even looking.”

“Guys, I'm so tense right now (while clenching fists) because you won't stop running around and screaming and I feel stressed out.”

In Others

“Ahhh, Nora's so happy that you gave her a big Peppa Pig for her birthday! Look how much she's smiling!!!”

“Aw, Bluey's sad her friend's moving away. Look at those tears in her eyes. She's gonna miss her!”

“Pete the Cat's tired of shoveling snow...look at his drooping eyes. He's about to fall over!”

In Your Child

“You look so happy that PopPop's taking you to get ice cream, look at that huge grin!”

“Your pouty lip tells me you might be sad Whitley cut you in line for the slide.”

“Is this monster scaring you because your eyes are glued shut so tightly?”

When your child's highly emotionally reactive, provide clues for the emotion, label it, and share how you can help:

“Are you SO excited you get some ice cream???! Listen to those shrieks of joy. Come sit down for it.”

Let your child know their feelings are a natural way to feel in that situation; that they're understandable:

“It makes sense to me that you're upset. I wouldn't like someone taking my toy either. I'm here for you. Let's see how we can make it right.”

Share the difference between feelings and ensuing actions if you want a different behavior:

“You were excited to see the puppies, but you can't run across the street. You can give them a big wave though!”

Model emotional regulation in yourself, talking yourself through it out loud so you little one can see someone else do it:

“Whew, what a day. I'm BEAT. I need to take 15 minutes and rest my body and my mind so I can be my best Mom self tonight. Honey, would you watch the kids until 5:30, please?”

5. Build Independence, Self-Esteem, and Problem-Solving

Teaching children who stutter how to be in charge of themselves, especially when stuttering can make them feel like they’re out of control, is another great way to build emotional self-regulation.

First, I challenge their black and white, all-or-nothing thinking. When they say, “I can’t!” I like to change it to, “You can’t yet” or “You can try.” When your child has trouble doing something perfectly, you can encourage them with, “You're still learning to [x].” Similarly, if your child says, “I always...” or “I never...” you can say, “You sometimes...” or “Most times...” instead. Life is almost always more gray than black and white. I have a few more go-to phrases I use to challenge all-or-nothing thinking inside my “Stuck to Speaking Handbook.”

I also like to teach positive self talk. The way you speak to your child turns into the way they talk to themselves. Instead of just saying, “Good job!” every time your child does something well, say exactly what they did that's good. That reinforces that specific behavior instead of the more general, “Good job.” Instead of saying, “I'm so proud of you!” teach your child how to talk positively to themselves by saying, “You should be so proud of yourself because...” or “You should be so impressed with yourself because...” Learning anything new can be difficult. Encourage your child through the hardship by reminding them, “You can do hard things.” Check out the other four self-talk strategies I love inside my “Stuck to Speaking Handbook.”

I also like to give choices. When they can be, being in charge *in constructive ways* builds self-esteem and independence that are important buffers for stuttering. As much as realistically possible, let your child choose things themselves throughout they day: what toys to play with, food they eat, books they read, and clothes they wear, etc. One way to allow freedom of choice for your child in a way that works for you is to give two choices you already approve of and let them pick between the two.

Finally, I teach them how to practice on-the-ground problem-solving, where you teach your child how to problem-solve for when you're not around. At first, offer different options for solving a problem and let your child pick which one they want to go with (e.g. wet paper towel or sink and soap to clean dirty hands). As you face problems in your own day, talk your way through them out loud, letting your child see how you come up with options and choose the best one. One of my favorite things I do when my child is upset is ask, “What would help make it better?” That way she has to think of a solution to self-regulate and I'm not just spinning my wheels. When feasible, expect your child to problem-solve on their own. “I know you can find a way to solve that” or “I know you'll find a way to make it right” are good options.

I have eight more suggestions for how to build independence and self-esteem inside my “Stuck to Speaking Handbook” right here.

6. Practice Grounding Themselves in the Moment

Mindfulness centers us and helps us understand what's going on in our bodies and our environments.

A recent meta-analytical review in the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association found mindfulness practice statistically significantly improved self-regulation in young, preschool children, with an effect size of .44 (Pandey et al., 2018).

From acting out things in nature, like a tall tree, a mighty mountain, or a lunging lion while being mindful of their bodies…

To taking a deep breath and letting it out for longer than the inhale (like six seconds) while doing something fun like blowing out a candle or blowing bubbles…

To getting deep squeezes and resting in that pressure…

To getting some Big Play like wrestling, doing a makeshift obstacle course, or rolling down a hill…

Getting grounded in the realities of their bodies can help children learn to regulate their nervous systems, which, in turn, can help them speak from an easier place.

Here’s a source. And another one, and another one. Oopsie, one more here too.

When Should You Get Professional Help?

Okay, so you’re armed with a ton of ways you can start helping your child stutter less and speak more easily but you’re still worried. Many people say “just wait-and-see” when it comes to stuttering and see if it goes away on its own.

And while that does work for the ~85% of children who eventually recover, it’s impossible to know for sure if a child will recover from stuttering or not at the outset.

But there are some well-documented “risk factors” for developing “persistent developmental stuttering,” or stuttering that doesn’t go away. Singer et al. (2020) completed a meta-analysis and found and ranked six risk factors for stuttering persistence, here in order from largest effect size to smallest effect size:

1. Any Family History of Stuttering (in Childhood or Lifelong)

The biggest risk factor for a child continuing to stutter is having any family members who stutter(ed). That means mom, dad, grandma, grandpa, Uncle Frank, or cousin Escobar. Because around 80% of one's predisposition to stuttering is genetic, this risk factor is the biggest, with a risk ratio effect size of 1.89.

2. Being Male

Many more boys continue to stutter on into adulthood than girls, making male sex the second biggest risk factor for persistent stuttering, with a risk ratio effect size of 1.48.

3. Poorer Articulation Skills

All children say certain speech sounds in funny, "cute," or different ways as they learn to say them. But having poorer "articulation" or "phonological" abilities, as they're called by speech-language pathologists, is the third biggest risk factor for persistent stuttering, with a Hedge's g effect size of -.54. Now, that doesn't mean your child has to have an actual diagnosed "speech sound disorder" for this risk factor to count, because in Singer et al's. (2020) meta-analysis sample, children with persistent stuttering had a standard score on an articulation test of 90, while their recovered peers got a 100 (a "standard score" of 100 in test statistics is "average").

4. Having a Higher Percentage of Stuttering-Like Disfluencies

Having more stuttering is the fourth biggest risk factor for persistent stuttering, with a Hedge's g effect size of .53, with the children with persistent stuttering in Singer et al's. (2020) sample having 8.7% of their syllables stuttered vs. only 6.1% of syllables stuttered for their recovered peers.

5. Having Poorer Receptive Language Skills

"Receptive" language means the words your child can understand when they hear them. Having poorer receptive language abilities, or not being able to understand as well, is the fifth risk factor for persistent stuttering, with a Hedge's g effect size of -.46.

6. Having Poorer Expressive Language Skills

"Expressive" language is the words your child knows how to say, regardless of how well they say them. Having poorer expressive language abilities is the sixth biggest risk factor for persistent stuttering, with a Hedge's g effect size of -.43.

Guitar (2013) also posited three other risk factors for stuttering persistence, that, while not found in Singer et al.’s (2020) meta-analysis, I think are still important to consider:

7. The Time Since the First Onset of Stuttering Being Greater than One Year

While virtually all children who will recover from stuttering do so within four years, by age seven, most of them do so within one year of beginning to stutter. If your child has been stuttering for over a year (whether continuously or off and on), that's a risk factor they may persist.

8. Having Stuttering Start Late (i.e. After 3.5 Years)

Ninety-five percent of children start stuttering before 48 months, or their fourth birthday. So starting to stutter late in that timeline, especially after three and a half years old, is a risk factor for persistent stuttering.

9. Having a Sensitive Temperament

Last but not least, Guiter (2013) posits a sensitive or inhibited temperament is a risk factor for persistent stuttering. While the least important, it's a good one to keep in mind and account for, especially if that's your child.

Deciding when to start speech therapy is a decision usually made by weighing three factors:

1. Time Since Onset

If it's been more than a 12 months, or a year, since your child first began stuttering and it hasn't gotten better or it's gone away and come back again, it's recommended to start speech therapy.

If it's been more than six months but less than a year since your child started stuttering, but they have many of the risk factors for persistence, it's recommended you start speech therapy (the more risk factors, the sooner you should start speech therapy).

If it's been less than a year since the onset of your child's stuttering but they have an awareness of their stuttering, especially negative reactions to their stuttering, you should also seek to start speech therapy.

If it's been less than six months since stuttering's onset and your child has no risk factors for persistence and no negative reactions to their stuttering, you can "wait and monitor" their stuttering (I recommend keeping tabs using the Stuttering Tracking Sheet above), until they trip one of the other factors for a stuttering evaluation.

2. Client or Parent Concern

75% of children who stutter seven and under have displayed at least one, unambiguous negative reaction to their stuttering (Boey et al., 2009). If your child is aware of their stuttering, especially if they're exhibiting negative reactions to it like:

1. Saying “Why can't I talk right?”

2. Saying “My mouth is broken.”

3. Hanging their head and giving up on a sentence

4. Crying or getting mad in response to stuttering

They should get help from a speech-language pathologist, no matter how soon it's been after stuttering's onset, be it six days, six weeks, or six months.

Also, if you, as a parent, are extremely concerned about your child's speech, you should honor your parent's intuition and seek to have them seen by a speech pathologist.

3. Risk Factors for Stuttering Persistence

Finally, if your child has any risk factors for persisting in stuttering, they should be taken into account when deciding if/when to start speech therapy. There's no magical formula here, but generally, the more risk factors a child has, and the bigger the ones the child has, the sooner you should see a speech-language pathologist, even if it's been less than 12 months or even less than 6 months since their onset of stuttering.

I give a lot of weight to a family history of stuttering and if the child's male, since those are by far the biggest risk factors for persistence. If one or both of those are present, I usually always recommend a stuttering evaluation and speech therapy.

For the remaining risk factors, while there's no perfect science, I usually move my recommended stuttering evaluation up by one month for each of those risk factors a child has.

You get a simple, one-page "When to Get a Stuttering Evaluation" rubric inside my full “Stuck to Speaking Handbook” so you can use to see exactly when you should get a stuttering evaluation for your child.

How Do You Get Professional Help?

So how do you get your child evaluated for stuttering by a speech-language pathologist? Well, it depends on how you'll be paying for it.

Through Health Insurance

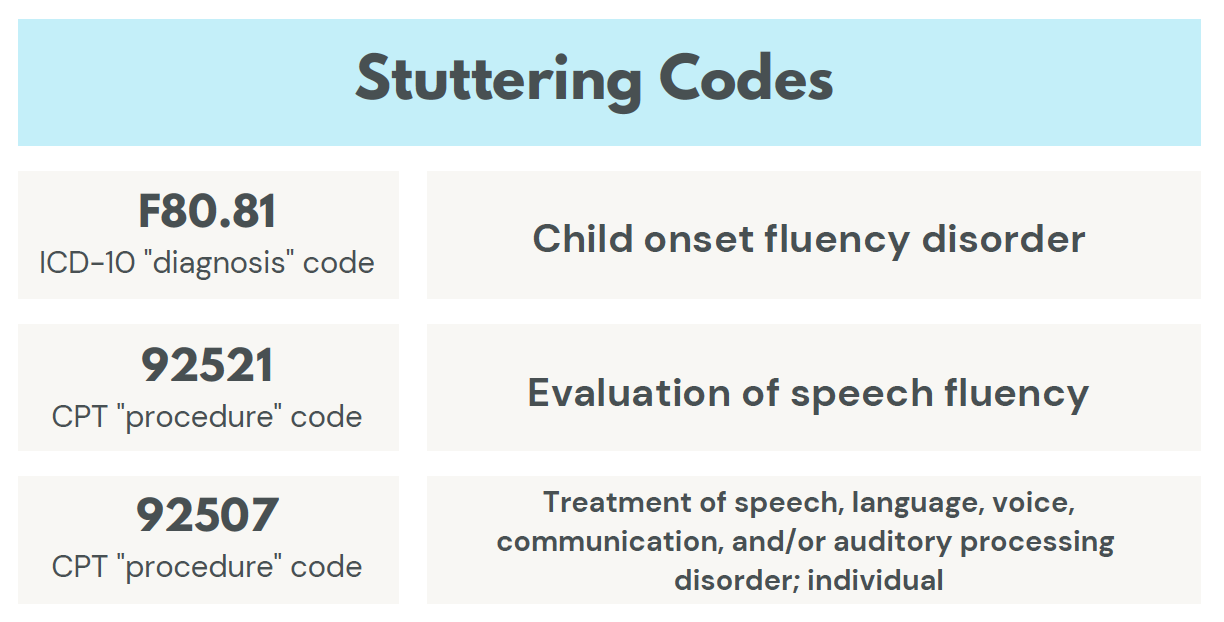

You don't need a doctor's referral to see a speech-language pathologist, however, insurance companies normally require a doctor's referral to reimburse speech therapy. To go this route, first call your insurance company and ask if they cover speech therapy for stuttering. Ask them if they cover the following "codes:"

"Child onset fluency disorder" will be the diagnosis your doctor gives your child so they can get speech therapy. The "Evaluation of Speech Fluency" and "Treatment of speech..." codes will be the ones billed by your speech-language pathologist when they assess and treat your child's stuttering.

These codes may be listed under the "speech therapy," "speech-language pathology," "physical therapy and other rehabilitation services," or "other medically necessary services or therapies" categories in your insurance's coverage.

If your insurance company does cover those "services," as they're called, next, call your child's pediatrician or family doctor, set up an appointment, and share your concerns about your child's stuttering with them, including:

1. The time since their stuttering first started

2. Any risk factors your child has for persistence

3. Reactions your child has made to their stuttering

4. Videos of your child stuttering at home (since stuttering can vary from day to day and situation to situation)

While many doctors take a "wait-and-see" approach, most will give you a referral to a speech-language pathologist if you insist.

They may have a speech-language pathologist they trust and refer out to, or they can refer you to an SLP of your choice, just double check they take your insurance first. Then you can set up an evaluation appointment with that SLP and get your child more help!

Private Pay

Alternatively, if you're going to pay out of pocket, you can “self-refer” straight to a speech-language pathologist of your choosing, contact them, and set up a stuttering evaluation for your child, no doctor's referral needed.

Speech-language pathologists are certified to practice in general in the U.S. by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association and licensed to practice in a specific state by the state's licensure board.

SLPs are currently only allowed to treat clients in states in which they are licensed.

While you might think every SLP would be equally qualified to treat your child's stuttering, that's not always the case. SLPs treat a very broad range of communication, cognitive, and swallowing difficulties from birth to death throughout the lifespan and not every one has experience treating childhood stuttering.

If you want to find a speech-language pathologist who specializes in stuttering in your state, start with these two great tools:

1. The Stuttering Foundation of America’s Therapy Referrals List

Go to “www.stutteringhelp.org/therapy-referrals” online and you'll find a list of stuttering specialists by state.

2. The American Board of Fluency and Fluency Disorders Specialists List

Go to “www.stutteringspecialists.org/findspecialist” online and you'll find another repository of stuttering specialists by state.

Now, not all the speech-language pathologists qualified to treat your child's stuttering will appear on one of these lists, but they can provide a good starting point in your search.

Early Intervention

If your child is younger than three years old, you can get free (or very, very cheap, depending on the state) speech therapy from your state through early intervention if your child qualifies by need.

Every U.S. state has to offer early intervention services by federal law under Part C of the IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act).

You, your doctor, your child's teacher, or social workers can all refer your child to early intervention services. To find the "EI" contact for your state, go to the CDC's contact list at: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/parents/states.html.

A coordinator will meet with you and decide if your child warrants further assessment, after which an Individualized Family Service Plan can be drawn up by your and the early intervention team outlining what therapy your child will get, when they'll get it, and where they'll get it (early intervention is usually done in your home, the child's “natural environment”).

No matter where you get help, you can find a checklist of the eight most important things you should bring to your child’s stuttering evaluation on page 106 of my “Stuck to Speaking Handbook.”

Want Even More Help?

Now, I only had time to cover some of what comes inside my “Stuck to Speaking: A How-To Handbook For Parents of Preschoolers Who Stutter” in this post (although I hope you still got a LOT out of it).

If you want ALL the tips, tricks, and techniques I have, you can get the full thing below for $47. Things like:👇

The Simple Model of Speech Production (do you know how it works?)

The Full List of Stuttering Symptoms (you seeing any of these?)

Top 3 Stuttering Myths (do you believe them?)

The Complete Breakdown of What Causes Stuttering (want to know all the neuroanatomy?)

Insight Into Stuttering’s Variability Over Time (will it come and go in waves?)

My Stuttering Tracking Sheet (where will you keep track of yours?)

The Fourth Technique to Slow Your Speech Down (to add to the other three above)

My Third Approach to Reducing Communication Demands (you’re gonna wanna know this one)

My Friends and Family Stuttering Script (do you know how to talk about it?)

The Two Things to Do When They’re Really Stuck (how can you help them out of it?)

The Differences in Temperament Statistics (your child seem sensitive?)

The Complete List of Emotional Regulation Strategies (so you can calm the speaking storm)

The When to Get a Stuttering Evaluation Rubric (calculate on one page when you should get help)

What to Do If Your Child is Bilingual (it’s not the same as for monolingual kids)

The 8-Item What to Bring to Stuttering Evaluation Checklist (do you have them all ready?)

Also, if you opt to invest in “Stuck to Speaking” Platinum ($97), you’ll get:

Live Demo Videos where you can watch exactly how I do the most important techniques inside Stuck to Speaking so your confidence can be through the roof.

A digital and physical edition of my children’s book on stuttering, “Unstuck” so you can be armed with a “cool way” to talk about stuttering with your child that doesn’t feel weird.

The Ask-Me-Anything Parent Q&A Forum where you can ask me any question about your child and stuttering and get my answer within 24 hours.

Do you wanna give your two to six year old the best chance to stop stuttering once and for all?

Want everything you need to help them speak stutter-free?

Then you want my “Stuck to Speaking: A How-To Handbook For Parents of Preschoolers Who Stutter” (plus the Platinum edition).

I want my copy of “Stuck to Speaking: A How-To Handbook For Parent of Preschoolers Who Stutter.”

Choose the price that’s right for you, create a quick login, and download the materials.

“Stuck to Speaking” Platinum

(PDF + Demo Videos + Children’s Book + Parent Q&A Forum)

“Stuck to Speaking Handbook”

(Just the PDF)

“Stuck to Speaking: A How-To Handbook (PDF) For Parents of Preschoolers Who Stutter”

“Stuck to Speaking: A How-To Handbook (PDF) For Parents of Preschoolers Who Stutter”

Live Demo Videos

“Unstuck” Stuttering Children’s Book (digital and physical)

Parent Q&A Forum

Too much for this month? Pay $37 for three months (total of $111) instead.